A Plan to Stop Cancer’s Spread

Dr. Maria Castaneda

Dr. Maria Castaneda remembers struggling in an undergraduate chemistry class at the University of Tulsa when a professor invited her to work in his lab. As she gained hands-on research experience, the course material began to make sense.

“I quickly fell in love with it. My grades went from one end of the spectrum to the other,” Castaneda said. “If it wasn’t for him asking me to do research, I don’t believe that I would have continued.”

Castaneda completed her chemistry degree and came to UT Dallas for graduate school. She thrived academically in the research lab of Dr. Jiyong Lee, assistant professor of chemistry, where she investigated cancer therapeutics that target metastasis and relapse.

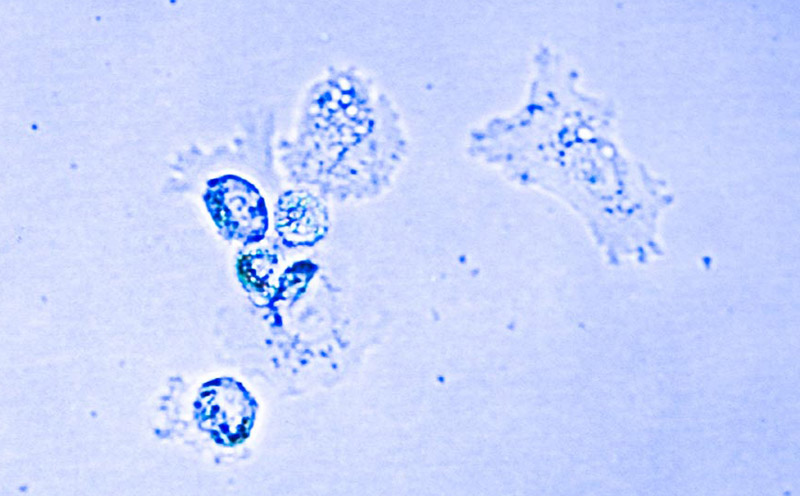

Backed by several research grants, Castaneda’s research has already netted results and a potential patent. She identified a synthetic molecule called MC-1-F2 that blocks cancer cells in a primary tumor from transforming into cells that metastasize. The transcription factor Forkhead Box Protein C2 (FOXC2) is needed for cancer cells to transform from epithelial cells, which don’t move, into mesenchymal cells, which are mobile. MC-1-F2 essentially puts up a roadblock to prevent cancer from spreading.

After earning her PhD from UT Dallas in May, Castaneda is continuing her research on FOXC2 as a postdoctoral fellow at UT MD Anderson Cancer Center in the lab of Dr. Sendurai Mani, co-director of the Center for Stem Cell & Developmental Biology and the Metastasis Research Center.

Mani’s group discovered that FOXC2 is a mediator of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

“That’s been the emphasis of my research: how to target that specific transition,” Castaneda said.

“Our group focuses on finding drugs that will inhibit the transition. His group works on identifying the pathways and where you can block the pathways. It’s really a continuation of what I did at UT Dallas.”

Castaneda’s interest in cancer research is personal. In her last year of high school, her grandfather in rural Mexico became very sick and was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

“The cancer had already metastasized to his bones. There was absolutely nothing that could be done, even less so in a country where you don’t have the infrastructure for hospitals. He passed three to four weeks after being diagnosed,” Castaneda recalled.

When she was about to graduate from Garland High School, Castaneda thought about pursuing cancer research, but didn’t know how to begin.

“My only concept of college was that it existed,” Castaneda said. “A guidance counselor sat me down and explained everything. We talked about my grandfather’s death. That’s when I realized there’s not a lot of new cancer treatments out there. There are chemotherapeutic drugs, but they have a lot of side effects that are almost worse than the cancers.”

She chose to study chemistry because she wanted to focus on how drugs are made. In the lab, fellow students would be frustrated when a chemical reaction didn’t work; Castaneda wanted to know why.

“You learn something from every failure. To me, sitting there for five or six hours purifying a compound, listening to music, it was OK. I liked it,” she said.

As an undergraduate, she worked three jobs until a scholarship enabled her to focus on her research. In her graduate work at UT Dallas, Castaneda expanded her research to understand how drugs are discovered.

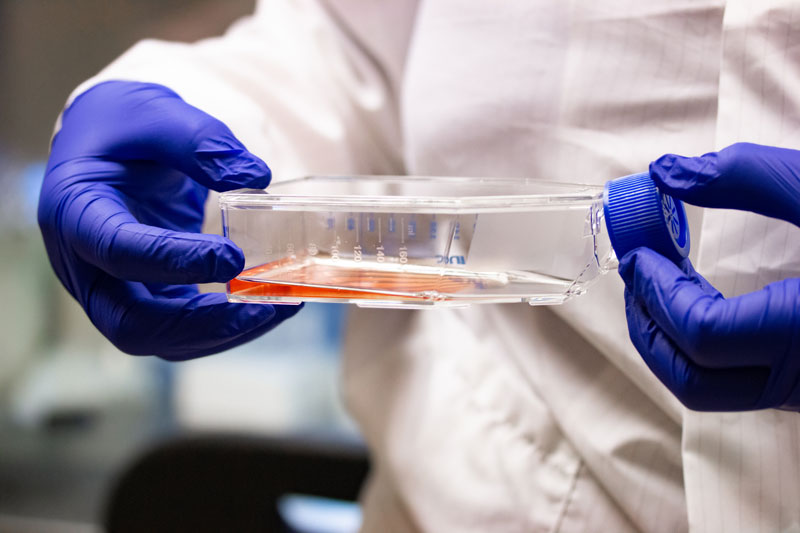

Dr. Maria Castaneda with research scientist Stefanie Boyd and research assistant professor Dr. Li Liu, both in biological sciences.

Bottom: Breast cancer cells are the focus of Castaneda’s research.

In July 2015 Lee’s research group was awarded a grant from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas to continue investigations on breast cancer stem cells. Castaneda also received a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship in 2016 and soon after was named a Eugene McDermott Graduate Fellow at UT Dallas.

Those opportunities provided her with a stipend and funding for research and supplies, and gave her opportunities to network with other scientists, attend conferences and write papers.

She focuses on breast cancer metastasis because of its high incidence rate — one in eight women will get breast cancer in their lifetimes — and low survival rates once the cancer metastasizes.

“We’re getting a lot better at treating cancer that’s localized because it behaves in a way that we know. But once it’s spread, we don’t know why, or why it’s spread faster in one person versus another, or why certain cancers like breast cancer are usually going to metastasize to the lungs. There’s still a lot to learn,” she said.

As a first-generation student, Castaneda said her biggest challenge has been dealing with her family and culture. Her parents grew up in small, rural Mexican towns and met when each had emigrated to the U.S. Neither of them understand Castaneda’s need for postgraduate research.

“My family thought, ‘OK, you go to university for four years, and then you get a job.’ Now my mom asks, “Why are you still going to school?’ They didn’t understand what graduate school was. They still don’t,” Castaneda said. “They’ve just accepted that I’m going to be in school forever.

“My mom wants to know, ‘Haven’t you learned everything already?’ I told her that if I had, we would have already cured cancer.”